Moving Clock in Special Relativity

What happens to a clock which is moved at some speed for some time. According to special relativity it runs slower on the move. Lets get a bit of an intuitive understanding of this.

Moving a light clock from here to there

I described the light clock earlier and showed how it runs slower when it is moving. Now, what if we have two identical light clocks, synchronized at some position. Then we move one by a distance $d$ and then stop again. Does it now

- run slower,

- lag

- and how much

- and can we actually measure this?

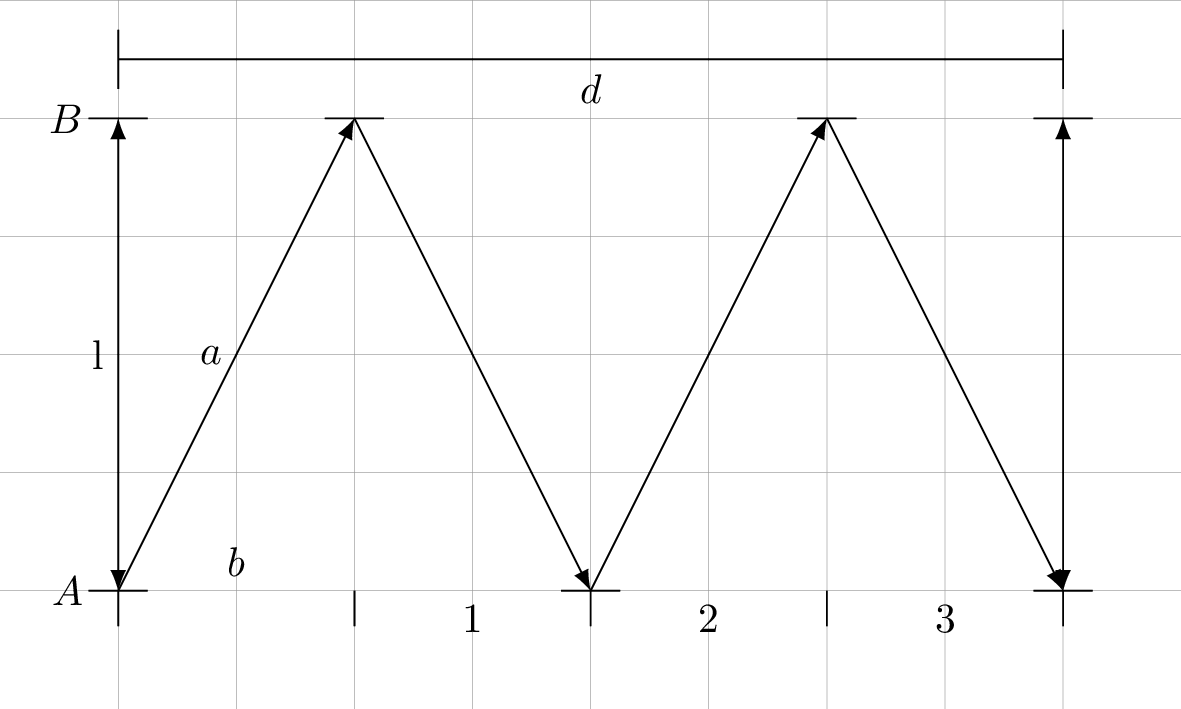

Consider the light speeding at $c$ along the light clock of length $l$ on the left of the diagram between $A$ and $B$.

A second, identical light clock is moved along the distance $d$. For simplicity, assume initially that we move the second clock with a speed $v$ such that it ticks exactly $n/2$ times during the move. A tick is one complete cycle of the clock where the light beam runs from $A$ to $B$ and back to $A$.

What is the speed component $v_l$ of the moving clock along $l$, the vertical axis? We have the speed $c$ along the diagonal $a$ and we have defined to move the clock with $v$ along $b$. Consider the time $T$ to be the time it takes along $a$, then $a/T = c$, $b/T = v$ and $l/T = v_l$. We also have $a^2 = b^2 + l^2$. Divide by $T$ to get $c^2 = v^2 + v_l^2$ or $v_l = \sqrt{c^2 - v^2}$.

How often does the moving clock tick until it reaches the end of the move? Since it moves with $v$ along $d$, the time is $T_d = d/v$. During this time, the total vertical movement of the light beam is $T_d v_l = v_l d/v$. Divide by $2l$ to get the count of the moving clock as $N_d = v_l d/2lv$.

Similarly the count for the stationary clock is $N_0 = cT_d/2l = cd/2lv$. The lag factor $L$ as the factor of how the moving clock ticks slower is therefore $$L=N_d/N_0 = v_l/c = \sqrt{c^2 - v^2}/c = \sqrt{1 - (v/c)^2}\,.$$ Should we not have found the Lorentz factor, not its inverse? No, it is just right, since the Lorentz factor relates the time between two ticks of the moving clock and the stationary. Since we count the ticks, we get its inverse.

Synchronized Clocks

What does this mean for clock synchronization: If I bring a well synchronized clock from here to there, I cannot avoid having the lag factor $L=\sqrt{1-(v/c)^2}$. But look, if the speed $v$ with which we move the clock is (nearly) zero, $L$ is (nearly) $1$, so there is no lag for very slow movement.

But how bad does it get? Can we measure the lag? Suppose we move a clock with an airplane and, for simplicity, assume it can do $\unit{1000}{km/h}$. We then have $$v/c = 1000\cdot1000/3600/299792458 \approx 9.27\cdot10^{-7}\,,$$ for a lag factor of $$L \approx 1-\sqrt{1-(9.27\cdot10^{-7})^2} = 4.3\cdot10^{-13}\,.$$

Now suppose we fly the clock $\unit{1000}{km}$ away, meaning the time of movement is one hour or $\unit{3600}{s}$. After the move, the moved clock lags by $\unit{3600}{s}\cdot 4.3\cdot10^{-13} \approx 1.5\cdot10^{-9}$ or $\unit{1.5}{ns}$.

Once we stop moving the clock, it runs as fast as before, but it is no longer synchronized: it runs with a lag which depends on the velocity of the move and the time it took — or the distance. Here you can experiment with different values.